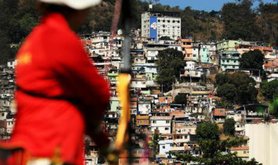

A police officer with an axe in the Macaco favela of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil during a mission against a criminal gang. Image: Humberto Ohana/PA Images, All Rights Reserved.

Massacres in Brazil show the relationship between the expansion of military justice and impunity.

The debate revolves around the expansion of the jurisdiction of the military (military justice, not common justice) to prosecute crimes involving civilians – be they defendants, or victims of human rights violations by members of the Armed Forces.

But massacres are not isolated events - far from it. Violence has increased since the federal intervention in Rio de Janeiro began in February 2018. According to the Intervention Observatory report, the facts are alarming: from February 16 to April 15, 1502 shootings were reported, which resulted in 284 deaths and 193 people injured.

In the previous period, from December 16 to February 15, 1299 such events were reported. Crossfires also produced 12 massacres and 52 casualties. In the same period in 2017, there were 6 massacres and 27 deaths.

There is a great risk that impunity will consolidate increasing violence. The Armed Forces High Command has established the territorial and institutional limits of the militarization process.

It will not be limited to Rio de Janeiro. As indicated by the Federal Public Security Controller of the State of Rio de Janeiro, Army General Walter Souza Braga Netto: "Rio de Janeiro is a laboratory for Brazil".

On one hand, it will not be limited to Rio de Janeiro. As indicated by the Federal Public Security Controller of the State of Rio de Janeiro, Army General Walter Souza Braga Netto: "Rio de Janeiro is a laboratory for Brazil".

On the other hand, it will require an institutional shield. Army Commander General Eduardo Villas Bôas does not mince his words when he says that it is necessary to give the military "a guarantee to act without the risk of a new Truth Commission".

To this end, the expansion of the jurisdiction of military justice, although little discussed, is crucial.

Military Justice: authoritarian origins and corporate organization

Historically, the structure of military justice has coexisted with ad hoc military tribunals which, under the Empire and the Old Republic, were widely used to deal with political contestation. From the very beginning, military justice bodies were mostly composed of military personnel.

In the early days, however, the Supreme Military and Justice Council, which was incorporated into the structure of the Executive Power, performed predominantly administrative functions.

Jorge Zaverucha and Hugo Cavalcanti Melo Filho have drawn attention to the fact that, with the expansion of jurisdictional activities, there was a tendency to reduce the number of military ministers and to gradually equate them with civilian ministers – this was finally achieved with the constitutional reform of 1926.

However, the rise of Getúlio Vargas to power marked an authoritarian turn which was not reversed in the following democratizing periods, and was in fact reinforced during the military dictatorship through Institutional Act No. 2, of 1965.

The Federal Constitution of 1988 left the institutional structure of military justice established during the dictatorship practically unaltered.

Today, military justice is comprised of the courts and military judges established by law (first instance) and the Military High Court (second instance). The Organization of Military Justice Act establishes that the first instance courts are to be composed of one civilian and four military judges.

Requirements for the post of the one civilian judge include legal education and having accessed a judicial career through open competition; the requirement for the military judges is simply that they be in active duty.

The same requirements apply for the second instance, composed of 10 military officers and 5 civilians.

The militarization of justice: the expansion of the jurisdiction of military justice

The 1988 Constitution succinctly states that military justice "is responsible for prosecuting military crimes as defined by law". What military crimes are and what will thus fall under the jurisdiction of military justice is defined by law.

This original (authoritarian) flaw of military justice was never altered by the democratic order of 1988, either by legislative or judicial means.

Two of these laws are direct legacies of the dictatorship of 1964: the Military Penal Code and the Code of Military Criminal Procedure.

The former establishes, for example, that crimes committed by civilians "against military institutions" are to be considered "military crimes" and thus fall under the responsibility of military justice (not ordinary justice).

This original (authoritarian) flaw of military justice was never altered by the democratic order of 1988, either by legislative or judicial means. There was an appeal submitted in 2013 to the Supreme Federal Court however questioning the jurisdiction of military justice to prosecute civilians (ADP 289).

Other legal actions question the legislative innovations which have expanded the competency of military justice in recent years even further.

These actions are aimed at provisions such as that of Complementary Law n.117 of 2004, which expressly establishes that the use of the Armed Forces in guaranteeing law and order is to be considered military activity for the purposes of applying the jurisdiction of military justice, and that of the LC n.136 of 2010 which defines as a "military activity" the use of the Armed Forces in "subsidiary activities" such as actions "against cross-border and environmental crimes" and "repressing crimes that have a national and international impact".

Recently, the Supreme Federal Court began to consider a direct appeal of unconstitutionality (n.5032) aimed at removing the jurisdiction of military justice in these cases.

Minister Marco Aurelio, acting as rapporteur, indicated that the jurisdiction of military justice and the use of the Armed Forces in guaranteeing law and order and fighting crime is constitutional. Minister Fachin disagreed.

And the investigation into the matter was suspended at the request of Minister Luis Roberto Barroso. Until the question of the unconstitutionality of the legislation that supports it is definitively settled, the Supreme Court authorizes the expansive use of military justice.

Over the last decade, this legislation was extensively applied in Rio de Janeiro when the National Force was used in "social pacification" missions in the favelas, resulting in several episodes of violence by members of the Armed Forces against the local population.

In July 2017, with the resurgence of violence and of the discourse defending the need to toughen repression of criminality, the Federal Government issued a decree authorizing the use of the Armed Forces for public security functions in the State of Rio de Janeiro – initially, until December 31, 2017, but the period was later extended to the end of 2018.

Calling on the Armed Forces for security tasks and even for surveillance duty in prisons has been quite common.

In this context, Law 13,491 of October 2017 was sanctioned by President Michel Temer and shortly after came into force. This new law extends once again the concept of military crime, this time to cover intentional homicide (with intention to kill) perpetrated by members of the Armed Forces against civilians.

This change means that the civilian police no longer have any power to conduct investigations into soldiers who kill in the exercise of their duties or in subsidiary activities such as in public security or policing tasks.

This change means that the civilian police no longer have any power to conduct investigations into soldiers who kill in the exercise of their duties or in subsidiary activities such as in public security or policing tasks. The investigations and the prosecution of these crimes – which were previously submitted to a jury – are now left in the hands of the military.

The new law, which violates the constitutional provision establishing the competence of the jury in such cases, is now in force. And the appeals questioning its constitutionality are pending to be heard by the Federal Supreme Court (ADI 5804 and ADI 5901).

But this is just one of the laws that make up the legislative constellation which is gradually strengthening the impunity of State agents who commit violations of fundamental rights against the civilian population.

In that sense, the federal intervention in Rio de Janeiro was defined as being of a "military nature" by the decree that established it which, in addition, appointed as controller an active-duty general who thus adds the functions of Secretary of Security to his regular functions as Eastern Military Commander.

Symbolically, the gradual expansion of military justice - especially in relation to civilians - denies Brazilian society the opportunity to consolidate its break away from the throes of authoritarianism and its commitment to democracy and fundamental rights.

In fact, it strengthens a return to the type of authoritarianism which has been manifesting itself politically and socially, as shown in the case of the recent military intervention in Rio de Janeiro, across the country.

The outlook

The militarization of security is phenomenon on the rise in Brazil and Rio de Janeiro is only the first step, according to General Villas Boas.

It is also an ineffective move for achieving its alleged purposes and a dangerous one too, for it promotes increased violence, violence determined by race, class, and territory of course.

Together with the expansion of military justice, impunity consolidates violence when faced up against the silence of institutions like the Supreme Federal Court.

As we have seen, military justice, the competency of which has been expanded in recent years, is partial and onerous. Lacking independence and impartiality to deal with civilians, it is an open door that leaves us more vulnerable as a society.

The institutional protection of impunity and corporatism which military justice provides confronts us with a tragic outlook: that of increasing violence and authoritarianism combining with the erosion of democracy and the rule of law.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.