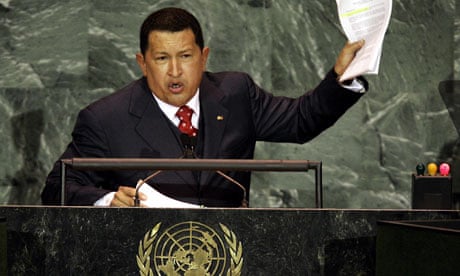

What form of democracy does effective development require? Now the pageantry of Hugo Chávez's funeral is over, and as Venezuela prepares for elections, this is an important question.

In development circles, a western liberal version of democracy is often presented as inseparable from development. Many donors make their aid conditional on this, either directly or through some proxy measure like "good governance".

Yet Chávez – in some respects the Beppe Grillo of Latin America, since he too swept to office on a wave of anti-political frustration – did the opposite. He used his country's oil wealth and his own popular mandate to refashion Venezuelan democracy in ways that he thought better addressed the country's long-standing development issues.

Predetermined ideas on what this has meant for basic human freedoms have polarised opinion about Chávez. From the left has come frequent – and frequently naive – applause at each initiative, even though many have assuredly been for the worse. The right, meanwhile, has proven unwilling to look beyond the mano a mano politics to see any good at all, looking back at pre-Chávez Venezuela as though it were some kind of prelapsarian democratic heyday.

The Bolivarian experiment warrants better than this. Chávez once admitted that, politically, he was a bit of everything (what else would you expect from a man who found his way to socialism through the Bible?). Accordingly, throughout his 14 years in power he played both radical and conservative, fair and foul, as he pursued one overriding (if paradoxical) objective: making Venezuelan society less unequal and more democratic, while remaining in power long enough to do so.

That meant, first of all, a new constitution followed by large, state-funded social programmes, or misiónes, which ploughed previously squandered oil receipts back into some of the poorest parts of the country. Per capita spending on health, for example, grew from $273 to $688 between 2000 and 2009, while the rate of poverty under Chávez halved in just more than a decade; extreme poverty fell by even more. Long overdue land reform was also implemented.

Inevitably, such policies met considerable resistance from Venezuela's elites, though not from all. After the attempted coup against him in 2002, and again after winning his second term in 2006, Chávez picked up the pace of change. Among his measures were educational enrolment, an outreach-style literacy campaign, local health initiatives like the Cuban-staffed Barrio Adentro programme, and other social projects – such as Vuelvan Caras – designed to get long-term unemployed people back into work.

At the same time, the original process of land reform was cranked up while the definition of how much land could be taken from individuals was loosened. The state took to meddling across a wider range of sectors: oil, gas, aluminium, the media.

But then Chávez never pretended his policies would be to everyone's benefit. Hence the establishment of Cuban-inspired Bolivarian Circles: community forums where participants would roll up their sleeves and get to work in the neighbourhood, and which conveniently served as Chávista support groups on the side. These and more recent participatory forums, such as the Communal Councils (intended to foster community development projects) and Urban Land Committees (which emerged spontaneously to address the Herculean task of allocating land tenure in slums), have increased local participation in the development process. But they have done little to address the equally pressing problems of endemic violence and lawlessness. A better organised state was required for that, but Chavez's state was too busy keeping its leader in power.

Democracy, Chávez-style, was always – indeed increasingly – informal and under-regulated in this way. If this made it a rather dangerous game, there were many prepared to take the risk, with Chávez's television and radio shows and his public assemblies all hugely popular. A good many western commentators were quick to sneer at the idea of a president singing on TV – the very picture of it smacks of government by Simon Cowell – but they were equally quick to garland with praise El Sistema's Gustavo Dudamel and the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra when they played in western concert halls.

Venezuela's Bolivarian experiment demands criticism and recognition in fairly equal measure. The Carter Center has stated its confidence (pdf) in the quality of last year's elections, for example. But democracy is about more than just the ballot box.

For Chávistas, of course, this is precisely the point: true democracy is a process, a way of conducting oneself in relation to others. It is not just a periodical duty to put a tick by a name. It is this that has made it such an interesting force for development. But if it is beyond argument that citizen participation rates have increased in Venezuela in the past 14 years, and that the political system has deepened to include the grassroots and the voices of poor people, it is not disputed that, under Chávez, political posts were stuffed with his supporters, judicial processes gerrymandered, judges cowed, and critical media sanctioned whenever its toe strayed across a highly diaphanous line.

Ultimately it doesn't matter that things under Chávez looked messy, or even that he departed from liberal democratic proceduralism. Wealthy liberal democratic nations have their own particular blindspots – including waning interest in active public participation, democratic deficits caused by structural injustice, and entrenched inequalities. The spirit of democracy matters more than the typeset of the letter and it requires constant reinvention to avoid being monopolised by the powerful.

Chávez was a breath of fresh air. He showed what can be done short of the revolutionary trick of slamming on the brakes and throwing overboard all those in the previous regime found enjoying the good life up on deck. But to reconcile the changes he wanted to make with the opposition he encountered, he sought to trademark his own model of a Bolivarian future. Such rhetoric simplifies, it snuffs out the flickers of dissent that effective democracy requires, and it risks making countries into things they are not. There is much indeed to learn from Chávez, but there is no reason we should learn uncritically.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion