Chiara Paez was 14 years old. She was a few weeks pregnant. On May 11, after a three-day search, her body was found buried in the garden of her boyfriend’s house. He was 16. Chiara had been beaten to death after having been forced to take medication to terminate her pregnancy. Her boyfriend, who confessed to the crime, had been helped by his mother.

A couple of months earlier, the body of Daiana Garcia, 19, was found by the roadside. Her remains were inside a rubbish bag. The body of another young girl, Melina Romero, was found a few metres away from a waste-processing plant last year. She had gone missing after celebrating her 17th birthday at a dance club. In another case, the body of Angeles Rawson, 16, was found inside a rubbish-compacting machine. All were victims of gender violence; and the list goes on.

Although official statistics are lacking, respected NGOs in this country – by compiling media reports – have calculated that a woman is killed every 30 hours because of gender violence. In the past seven years, more than 1,800 women have been killed in such circumstances. Given the absence of official reporting on femicide, this number is likely to be just the tip of the iceberg.

Where once these gender crimes, in most instances against a partner or former partner, were likely to be committed in domestic settings, in many recent cases they have made a leap into the public sphere – into coffee shops and classrooms. “Macho” gender violence has taken on perverse new forms and entered new spaces in Argentina.

Questions abound but there is one that rules over the rest: are more crimes being committed, or is it that they have become more visible?

Whatever the answer, it was on the day they discovered Ciara’s body that the idea to demonstrate was born; to take to the streets and shout “stop femicide”. The seed was a tweet in which Marcela Ojeda, a radio journalist, challenged women across the country with a phrase that is already historic: “They are killing us: Aren’t we going to do anything?”

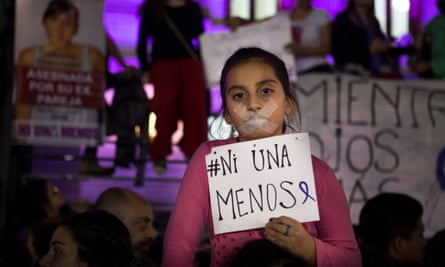

Some of us decided to do something. We protested, rallying around the slogan and hashtag #NiUnaMenos (“NotOneLess”, meaning we must not lose one more woman to violence).

The main march was to the congress in the capital city of Buenos Aires, where I and the other female organisers were astounded at the size of the crowd. Groups of women from outside the city arrived bearing photos of their relatives, slain victims of femicide. Some of them yelled their disappointment at the failure of the police and the courts to respond adequately. “I don’t want you to tell me how to dress,” read one of the handwritten placards.

For the three weeks before, a group of female journalists, intellectuals and activists had come together, explaining to others why we needed to march. We underlined that Argentina has comprehensive anti-gender violence legislation, but the law has not been fully implemented. Budgets need to be assigned. Security forces and justice officials need to be trained in how to deal with women who wish to report violent partners. An official register of femicide cases needs to be established.

We asked actors, television hosts and friends in showbiz to help. They each posed for a photo holding a sign reading #NiUnaMenos. Then, anonymous men and women, groups of friends, workmates, students, families and young children started doing the same. Politicians also joined, but only after the hashtag and the issue were already on everybody’s lips.

Before we knew it, in homes, schools, shops, on television, everywhere, people were talking about the issue. Young children grasped the concept and could explain to others that #NiUnaMenos was a campaign to eradicate violence against women – proof that our bid to raise awareness was beginning to bear fruit.

When we started to promote our cause we were just a handful of women. But soon we were hundreds and then thousands.

From the beginning we knew that what we wanted was not, or at least not exclusively, some form of collective venting of frustration. We wanted to ask for concrete action, not only by politicans and the justice system, but also by other sectors of civil society such as the media. We wanted criticism regarding the way these cases are presented, often focusing on the lifestyle of the victim, revictimising them again and again because of the way they dressed, the men they dated or the kinds of photos they posted on Facebook.

And it was also a call for solidarity. We need to help woman experiencing domestic violence out of the spiral.

The silent cry of women who suffer or have suffered domestic violence broke out of hundreds of thousands of throats that afternoon. This wave of violence must be stopped. Not because it is a noble cause. It’s something much more basic. It is a human right.

Barely 24 hours after the march ended we had the first piece of good news. Supreme court justice Elena Highton announced a registry of femicides would be set up at the court. The office of President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner set off a series of tweets emphasising her government’s concern. Meanwhile, the government’s Human Rights Secretariat announced it, too, would start to compile statistics on femicides.

Most important of all, judging by the massive turnout at the march, the majority of us now understand that looking away is no longer an option.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion